Dulwich Gallery is staging a rather

intriguing exhibition at the moment.

Entitled “A Crisis of Brilliance”, it in effects sets out to provide a

fuller visual accompaniment to the book of that title by David Boyd Haycock

than he was able to do in the confines of a “normal”, non-coffee-table,

book. It this he set out to tell the

entwined stories of six artists- Stanley Spencer, Paul Nash, Richard Nevinson,

Dora Carrinbgton, Mark Gertler and David Bomberg- in the wider context of the London

It’s a really interesting and well written

book about a more than averagely interesting (if not always likeable) group of

people, with an intriguing supporting cast like John Currie, a highly talented

contemporary and associate of the chosen six who shot his model/lover and then

committed suicide just before the outbreak of the War, and Isaac Rosenberg,

another Slade alumnus now better remembered as a poet killed in action in 1918

(and incidentally one of the very few War Poets who wasn’t of at least middle

class origins and didn’t serve as an officer).

I’m not going to try to summarise its content; I’d advise anybody who

takes an interest in the art of this period to read Haycock. For the purposes of this blog I’m just going

to focus on a few points which particularly struck or interested me.

The first of these was just how

conservative the Slade actually was by about 1910. It had a considerable reputation for being a

progressive sort of place artistically and maybe by comparison with other art

schools in London

Tonks was also violently hostile to just

about every development in modern art in Continental Europe postdating

Impressionism. He was driven to fury by

the two major shows of “Post Impressionist” art staged by Roger Fry in 1910 and

1912 and made it abundantly clear that he would have much preferred it had his

students not visited them. He can

hardly have been happy that Spencer actually exhibited in the second one. While there’s a case to be made that Fry was

motivated as much by self- aggrandisement and the profit motive (a good going

scandal was guaranteed to pull in the crowds) as a genuine desire to bring the

wonders of modern art to the benighted heathen of London, it was a remarkably

inward looking attitude. Obviously Tonks was a hardly alone in his views, which

were shared by most- though not all- of the British media and art establishment

of the day, but it left him aligned with the sort of people he wouldn’t

normally have given the time of day to.

Of course the sextet in question all

defined his wishes and in their different ways became deeply involved in the

deeply fissiparous and quarrelsome little world of modernist art, London

Looking at the art the chosen six produced

in this period, however, it’s abundantly clear that much of the shouting and

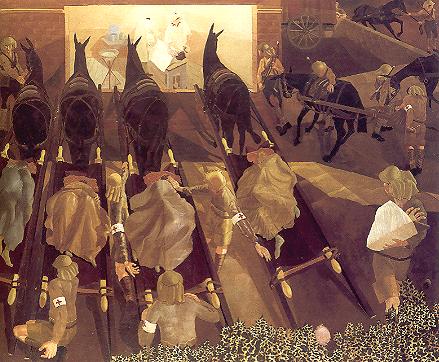

name calling was a case of the fetishism of microscopic differences. Bomberg’s “The Hold” pictured at the top of

this piece is about as Futurist a piece as one might hope to encounter (and a

good deal closer in style and approach to the art of Severini or Boccioni than

anything Nevinson was doing at the time).

It certainly reduced the “Jewish Chronicle” to baffled incomprehension-

and given that both Bomberg and Gertler were only able to attend the Slade

because they were beneficiaries of scholarships awarded to promising Jewish

artists that paper’s views mattered.

Gertler’s relatively conservative portraits of family members and East End rabbis, though only partially representing his

own preferences, were much more to the taste of the board which managed the

bequest which paid his fees- and of Tonks.

The rather odd picture of apple harvesters below would just about have

passed muster as well, with its clear echoes of classical and Renaissance art

(though I have to admit I find it rather lumpish and slightly creepy).

One can only speculate how the artistic and

personality issues would have played out had war not come in 1914. It’s a pretty obvious truism that this

deeply marked the lives of all six.

Intriguingly the only one to be part of the rush of volunteers to the

colours in September 1914 was Bomberg, who was initially rejected by the army

(evidently the recruiting officers didn’t quite know what to do with a rather

hairy Jewish artist…). Admittedly none

of the men (apart perhaps from Nash, whose later health issues appear to have

been at least in part a consequence of war injuries) were prime recruiting

candidates. Spencer only just scraped

the minimum height requirements; Nevinson and Gertler both had serious health

problems.

Despite his health problems, Nevinson was

the first to get to the Front. He, more

than most, ought to have had some idea what he was letting himself in for as

his father was a notable newspaper war correspondent. Nevertheless his Futurist principles meant

that intellectually he approved of war as a form of social hygiene and felt he

should live up to his principles by taking part. Somewhat ironically he volunteered for

service with the Friends’ Ambulance Service, established and largely staffed by

Quaker pacifists who wished to do humanitarian work (mostly with the French

forces, whose medical services were initially overwhelmed by the scale of

casualties). This evidently made for

some lively discussions between Nevinson and his colleagues, though it’s fair

to say that Nevinson’s own views shifted to and fro several times once he had

been exposed to the realities of war.

Predictably his health broke down and he

ended up back in London- Britain

Inevitably the war impacted on all six

artists. The upper middle class Nash joined

up as an infantry officer, the less socially prominent Bomberg and Spencer went

into the Royal Engineers and the Royal Army Medical Corps respectively. Nash’s front line service was brief; he was

invalided out after falling into a shell hole and seriously damaging his

ribs. Bomberg self-wounded and was very

lucky not to be detected- he could easily have faced a firing squad otherwise. Spencer ended up in the mountains of the

Macedonian Front (where my grandfather served- I wonder if they ever met). Gertler became a Conscientious Objector

(though he can’t have been as absolutist in his views as some, since he went

through with the medical examination which accompanied the establishment of

conscription in Britain in 1916, duly failed it, and never appears to have had

to go before a tribunal to justify his position). Unlike many young women, Carrington was just

about well enough off not to have to go into war work to support herself,

though the war hit her as hard as any through the loss of a brother to whom she

had been very close. There was enough of

a well-heeled progressive anti-war counter-culture to provide a support network

and commissions for Gertler; Carrington’s profound lack of artistic self

confidence limited her output. She also

eventually dumped Gertler in favour of the writer Lytton Strachey- a somewhat

improbable relationship given that he was notoriously gay, though Carrington

was herself bisexual and as a relationship it clearly worked- at least on some

levels.

Perhaps the most unexpected outcome of the

war from a purely artistic point of view was the massive expansion of state

patronage which it offered both during and in the immediate aftermath of

hostilities. One major aspect of this

was the establishment of a formal “War Artist” scheme which recruited artists

and paid them to produce war-related art.

Those who went to the Front were given commissioned officer status and a

fairly free rein- though subjects were sometimes suggested. Though the “top management” of the scheme

were artists of an older and more conservative generation, there was absolutely

no control over painting style and modernists were welcome to apply. This proved a godsend for men like Nash and

Nevinson whose health-based exemptions from further service were beginning to

look tenuous as the pressure to find men for the Front mounted in 1917. They could now serve under conditions of their

own choosing. This didn’t necessarily

mean sitting in safe rear areas- Nash in particular used his skills as a

landscape artist to depict the sheer devastation of the Ypres

salient in a series of powerful works.

It was however probably safer than being an infantry subaltern with a

theoretical average life expectancy of six weeks. Even Gertler found merit in the scheme on

corporatist grounds (as favouring younger artists) and was initially prepared

to participate, though he finally backed out because he found he couldn’t

create something that satisfied him with the topic he had been pointed towards

(people sheltering from air raids).

Not everybody was included in the scheme

straight away. Spencer, far away in Macedonia

Other opportunities briefly opened up in

the immediate post war period. One

doesn’t normally think of Lord Beaverbrook- newspaper tycoon and Conservative

politician- as a patron of modernist art but in his role as head of Canada Paris Palestine

The other five enjoyed varied fates. Gertler never quite found a solid footing in

the post war art world and was doomed to be seen as someone who had not really

fulfilled his early promise. The works

shown in Dulwich (which admittedly exclude some of his best paintings) suggest

that even then he struggled to develop a truly consistent personal style. Impoverished, marginalised and ailing, he

committed suicide at the outbreak of the Second World War. Carrington’s diffidence about her art became

ever more overpowering, not helped by a complex private life spread between

Strachey and a series of lovers of both sexes.

She more or less gave up art altogether and when Strachey died in 1931

she chose to take her own life.

Nash’s war landscapes established him as a

major figure in British art, a status which he enjoyed for the rest of his life. Best remembered for his landscapes, he also

dabbled in his own brand of Surrealism and lived to see service again as a war

artist in the Second World War where he painted the vapour trails of aerial

dogfights and downed German bombers being absorbed into the English

countryside. Nevinson, by contrast,

never regained the status he briefly held during the war. His post-war works were, to put it charitably,

of variable quality- as in truth his war time works were also (there is, for

instance, an unpleasant undercurrent of misogyny and possibly anti-Semitism in

some of the pieces he produced away from the Front in this period). He

tried and failed to break into the American market and ended his days a

half-forgotten figure. It is an irony

that a small number of his works from his fifteen minutes of fame have now

acquired iconic status, visual clichés for the covers of books about the First

World War.

Spencer had always been a sturdy

individualist, deeply rooted in the Thames-side rural village of Cookham

Like Nash, Spencer lived to see artistic

service in the Second World War. His

area of activity was far away from rural Cookham, in the Clydeside

shipyards. There he drew the workers

toiling in the noise and ordered confusion of shipbuilding. His work there was something of a throwback

to the days of careful figure drawing at the Slade- Tonks would have thoroughly

approved.

No comments:

Post a Comment