I suppose I’ll get the my moans about the

National Gallery’s exhibition centred on the depiction of music in 17th

century Dutch art out of the way up front.

Although Vermeer’s name figures in the official title, there are only

five actual Vermeers in the show; clearly his name and reputation are being

used to pull the marginal punter through the doors. The said punter might also feel a bit done

down at paying almost full blockbuster price for an exhibition which (with the

exception of a couple of the Vermeers) is drawn entirely from the Gallery’s own

collections. None of the paintings on

display have come from outside the UK

On the positive side (if you happen to be

in the gallery at the right times) there are a series of short concerts given

by an early music duet which highlight music from the same period as the

paintings. This is genuinely intriguing

stuff as few 17th century Dutch composers bar the keyboard

specialist Sweelinck are at all well known even to early music enthusiasts like

myself and it appears the folk doing the concerts have had to undertake quite a

bit of archive research to assemble a repertoire for the event (sadly not

included in the tie-in CD being marketed by the Gallery).

Moans apart, the exhibition picks up on an

interesting theme. Music was deeply

embedded in 17th century Dutch culture (as indeed it was in all West

European cultures of that era) and paintings depicting the making of music

clearly found a ready market amongst the picture-buying public. There were even more direct linkages between

the worlds of painting and music too; it was common practice for virginals and

other keyboard instruments to be sold “plain”, with the purchaser commissioning

an artist to decorate them-as with the instrument depicted by Vermeer at the

top of this piece. Indeed Vermeer himself is thought to have done work in this

field, though no instrument whose decoration can be securely attributed to his

hand appears to survive Artists often owned musical instruments; it’s a source

of some surprise that none appear in the inventory taken after Vermeer’s

death. On the other hand, the social

profiles of the two arts varied a bit.

Musical participation was much more widespread- there would certainly

have been vastly more people around who would have been capable of picking out

a tune on a lute or a keyboard than could ever have hoped to draw or paint in a

competent manner (in that respect not much changes- music in one form or

another must surely still be the most common participant art form in the modern

world). Social elites who would never

have dreamed of dabbling in the manual labour involved in painting were happy

enough to perform music to (admittedly intimate and socially selective)

audiences-though there was always a tension between music as the necessary

accomplishment of an educated individual and music as a trade undertaken by low

status professionals.

Musical performance thrived further down

the social scale too, in the Dutch equivalent of pubs and dance halls- not to

mention brothels. According to the

catalogue for the exhibition there were drinking establishments which

specialised in music to such an extent that they had musical instruments hung

up on the walls for use by the clientele and even a fines policy under which

any visitor who was capable of playing a musical instrument but refused to do

so was expected to treat all those present to a drink (how did they check the

musical abilities of people who weren’t regulars?...). It is, incidentally, an interesting comment

on the collecting priorities of an earlier generation of British enthusiasts

for Dutch art that the exhibition contained hardly any paintings of music

making at the more plebeian and raucous end of the spectrum- not a chaotic and

ribald Jan Steen drinking den in sight, for instance. While not all the music on display is

necessary as decorous as it looks at first sight, one dimension of lived

musical experience of the Dutch Golden Age is a bit marginalised.

This experience was a little bit different

from that elsewhere in Europe . The United Provinces of the Netherlands Netherlands

On the other hand there was a large,

well-off mercantile elite- natural purchasers of musical instruments and

tuition on how to use them (or how to sing along to them). In addition to a lively world of home music

making, they were also potential patrons of and participants in local and

regional music societies. This was a world open to both genders (it’s

interesting that Vermeer’s “music” paintings invariably show women playing

instruments, usually keyboards, though the lady below is being rather

innovative and daring in trying out a guitar, a rarity in the Netherlands

Judging by the paintings in

the show, music also created an environment for legitimate interaction between

young people of different genders, not to mention flirtation - a bit like

tennis in the late 19th century, perhaps- the Metsu example below is

just one of many examples of that form of social interaction on display.

Less well filled purses still had access to

song books- a staple of certain Dutch printing houses- and you didn’t need to

be able to read music in order to participate.

A lot of music was probably learned by ear and song books were

frequently printed on a “words only” basis with an indication that they should

be taken to a well-known tune of the day- the wonders of common metre…..

The sheer omnipresence of music in daily

life meant that it could be taken as a metaphor for all manner of different,

sometimes contradictory, things in painting.

It made a very obvious visual correlative for hearing in paintings which

allegorised the five senses which are often set in musical dinners. The ephemeral nature of all performances in a

world before sound recording made a nod to music common in so-called “Vanitas”

paintings which made a disabused commentary on the basic vanity of human

ambition and worldly glory, all come to dust.

A musical instrument or a piece of sheet music joins swords and skulls

and learned tomes and fading flowers to drive home the moral (one of the

examples of this genre in the exhibition provides an interesting variant by

including a Japanese samurai sword- a symbol of trading empire as much as

military glory).

Perhaps the most obvious “meaning” of music

was as a way of symbolising harmony at all levels in society. This was a virtue which perhaps needed more

stress in the Dutch

Republic Holland (just one out

of seven) and, within Holland , the dominance of Amsterdam

It’s easier to see references to harmony at

the micro, household, level in this art- full of references to what appears to

be family music making as it is. This of

course could easily shade into the flirtations mentioned above- and in turn

shade into a rather more equivocal view of music. As I noted earlier, the most raucous and

disruptive associations with plebeian misrule don’t get many outings in the

exhibition. Sexual innuendo of one kind

or another is however very much on the agenda.

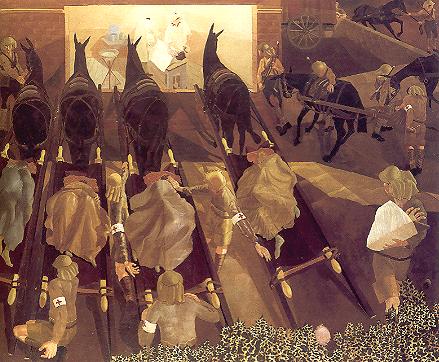

Take the music party painted by Jan Olis below. The room is suspiciously bare and the rather

louche looking collection of men relatively drably dressed (I wonder if they’re

meant to be soldiers off duty). By

contrast the only female present is a blaze of brilliant colours as she saws

away at the bass viol. This would have

been regarded as highly indecorous and unladylike- it was not an instrument

which ladies generally played. The

obvious inference is that she’s no lady and this isn’t a cosy domestic dinner

party…..

As also noted above the bass viol appears

to have been viewed as a standing metaphor for femininity and, by extension,

sexual innuendo, as was the lute (especially the large version, the archlute or

theorbo. Even when they’re not being

played, bass viols pop up suggestively among the props in many of the

paintings. One of the Jan Steens which

does make it in shows a young lady practicing on the clavichord under the

watchful (lustful?) eye of a young man; in the background a servant approaches

carrying a theorbo. One can guess

what’s going to follow, and it probably goes beyond getting the bass lines

right for the next family concert. I

did sometimes suspect however that this sexualised reading was getting a bit

overdone- surely there must be paintings in which a bass viol is just a bass viol….

The Vermeers in the show have their share

of bass viols among the scenery but their tone is rather different. Only one of them, the so-called “Music

Lesson” below, contains more than one figure- it’s assumed that the young man

is singing because he has his mouth open.

Young ladies practice their music in what are clearly the houses of

wealthy members of the civic elites- even their instruments are top quality

(the virginals look like top range Ruckers products, for instance). Presumably they’re daughters of the house,

well dressed and nice looking. They’re

probably primarily self-accompanied singers rather than keyboard (or guitar)

virtuosi- the type of virginal in use is a “muselar”, a model purely produced

in the Low Countries and used almost entirely to accompany singing (depending

on who you read, it had a particularly mellow tone or sounded like the grunting

of young pigs…). As with so much of

Vermeer’s mature art, we may be invited into their space but we’re also kept

rather at a distance. The guitar player

seems more interested in someone out of shot to our left, the couple are more

taken up with their own interactions than with anybody else; even the young ladies

who appear to make eye contact with us are still busy with their practice and

likely to turn away again any moment. There’s

a sense that the viewer is a distraction- who may or may not be a welcome

one. It’s a distinctly cooler and more

reserved world than that portrayed by most of the other artists represented in

the show. I can’t imagine any of

Vermeer’s subjects in a noisy Jan Steen tavern- or even having a riotous

concert at home full of booze and flirtation.

I also have a faint sense that that might have been their loss……